There’s a stereotype of expats in Mexico — that they try to stretch their income and that they isolate themselves from their Mexican neighbors. Granted, such people exist, but several Facebook groups show that this is not always the case. One is Women Surviving Rural Mexico.

Camille E. Torok de Flores started the group about three years ago, building on a series of books based on her experience living near Moroleón, Guanajuato, on the border with Michoacán. It is only two hours from the Guanajuato expat enclave of San Miguel de Allende, but it is a completely different world.

So, how did she end up there? Well, love had something to do with it.

Torok, who grew up in Pennsylvania and got her teaching degree at the University of Nebraska, took part-time work at a Mexican restaurant in order to improve her Spanish; that’s where she met her husband. He had immigration issues before and after they were married, and the couple finally decided to “deport themselves” in 2006.

They initially moved to the “city” of Moroleón, which has a noted rebozo (traditional Mexican shawls) industry. The couple bought a plot of land on the outskirts of town in the developing neighborhood called La Yacata but found that their purchase “wasn’t the best decision,” she explains.

Although their land is only two kilometers outside the city, “I can see the last electric post from my house,” she says. “I just don’t have access to it.”

She began a campaign to get La Yacata electric, water and sewer service, to no avail. “But I learned a lot,” Torok says.

Solely due to economics, they moved into the partially-built house. With no electricity, they had to go into Moroleón to do everything, including charging cell phones and laptops. At home, Torok learned new skills like washing clothes by hand.

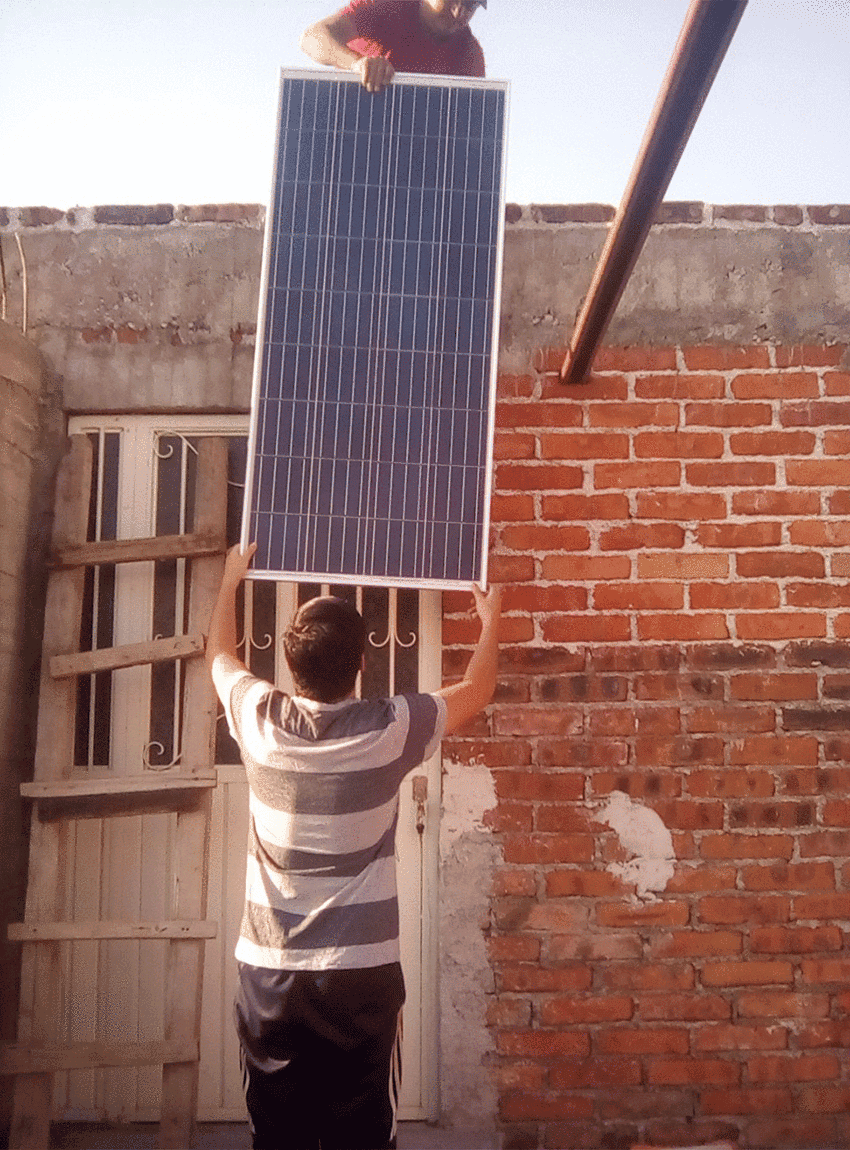

Finally, she got an online teaching gig, which paid enough to buy a solar panel setup. It provided basic electrical needs, but internet service would have to come later, she realized.

Her family teased her that if she had wanted such a lifestyle, she could have married an Amish man in Pennsylvania.

Fifteen years after arriving, “I finally got to the point where I am comfortable,” Torok says. Not having electricity for 10 years was “exhausting,” but now she can enjoy living in the house her husband built. It is better than anything they could have afforded in the United States, she says.

Before she came to Mexico, Torok had looked for books with practical information about living here but found none. Unprepared for rural living, she learned by trial-and-error, taking notes and sharing her experiences with her family through a blog.

Over time, these notes and blog posts turned into online books published through Amazon, starting with A Woman’s Guide to Living in Mexico. Torok focuses on practical advice, much of which is applicable even to those of us not living in the middle of nowhere. They are at their best when Torok speaks directly from personal experience.

The books are particularly important to women who come to Mexico because of marriage or family, often without any idea of what to expect.

The biggest challenge, by far, is the sense of isolation. Although Torok grew up in a pretty rural area, “I was never an outsider in my town,” she says, “and here, I am.” Even after 15 years, her interactions with the local community are more superficial than the relationships she has with old high school friends online.

One reason, she says, is that many rural Mexicans, especially women, are not comfortable with outsiders, preferring to keep their circles of friends as they have always been. In addition, these women are suspicious of outsider women who chat with their men — who can be easier to talk to because they have lived and worked in the United States.

Foreigners’ isolation can even be an issue with the Mexican spouse’s family members, who often expect that the outsider in their circle will not adapt to Mexico and eventually return home — which does happen.

Although most in La Yacata know her, most do not know her name. “I am la gringa de La Yacata,” Torok says.

Some in the community have at least tried to change this sobriquet to la maestra (the teacher), but Torok laughs and says that people just look puzzled by this until it clicks and they say, “¡Ah sí, la gringa!”

She emphasizes that it is not out of disrespect; she simply stands out that much.

Her books have been a kind of release for Torok, and three years ago she added the Facebook group since she can provide and receive emotional support through it (and maybe sell a few books).

Most participants in the Facebook community are from central Mexico, with some scattered in other places.

She has quite a few fans, including Ashlee Brooks-Diego of Venustiano Carranza, Puebla, who says Torok is “dedicated to helping women through a very emotional time in their lives.”

“[The Facebook] group has given me reassurance on many things and fears I have had along the way,” says Samantha, a member living in Chiapas.

Overall, Torok has no regrets for leaving the first-world lifestyle of the U.S. behind.

“There is a kind of lawlessness [in Mexico], but it also brings a type of freedom. You can create a different sort of life without the pressures from … family, friends or society in general,” she says.

In the United States, things are so busy and so expensive that she could not have the lifestyle she has now, Torok says. “I wouldn’t have such flexibility. Here, I have been able to create a life that I like, where I can do things like write these books.”

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.